This year will be forever linked to the global pandemic. It is our shared 2020 experience. Here in France, we are in our second confinement. We're to stay at home, leaving the house only for specific reasons such as grocery shopping, emergency care, or travel for essential work. Tentatively, lockdown will last until December 1st but many believe it will extend through the holidays and into the new year. Whereas last spring found me busy outdoors, working in the garden or foraging in the forest, this time the cold of the winter will make quarantine more challenging as we are confined in our tiny house.

While it has been a year of uncertainty, there is story after story illustrating communities across the globe coming together to care for the most vulnerable. The earth was given a small opportunity to heal. Global pollution levels dropped revealing blue skies over major industrial cities such as Beijing. Oceans and polluted waterways improved as tourism and cruise travel ceased. It’s unclear if the global lockdown measures will have long-term benefits for Mother Nature. Still, I’m hopeful there will be some positive change in the near future.

The pandemic is a testament to both personal and national resolve.

Quince. That forgotten fruit that everyone mistakes for a strange apple. In spring, the flowers yield a delicate pink / purple color. It’s a bit fragile for a dye on its own. But blended with summer rose petals and it produces a wonderful ink or watercolor. The process takes patience. You harvest the flowers and macerate only the petals with a mortar and pestle. Then, you place them in a glass jar and pour boiling water over top, allowing the mixture to sit in the sun for a few weeks. Reduce the liquid over a low heat, combine with a dab of honey as a stabilizer, and clove as a preservative. Voilà! You have created a one-of-a-kind color.

What we have been given in abundance during this difficult year is the precious gift of time. Time to rest, reflect, and rethink our priorities. We discovered that fast-pace living hurts our ability to think, innovate, and be creative. With more time, we can be mindful and appreciative of everyday life. Not to rush through our daily tasks. Rather, we pause, practice patience, and consider our purpose. The pandemic found me when I really needed to hear this message.

Fortunately, I live in the French countryside on a fairly secluded property with 9 hecteres of fields and forests. Warm days allow me to take long, slow walks, foraging for dyestuffs and using them to create handmade inks and watercolors. Cowslips in spring. Wild berries in summer. Walnut hulls in autumn. Lichens in winter. There is color to be found in every season. Confinement provides time to learn about local plants, how to extract the color, and experiment with application. This year, I realized that rushing through my walks, counting steps and determining progress kept me from noticing color possibilities. I’ve shifted to a closer connection with nature.

Over the past year, I worked with plant materials to create a collection of handmade natural inks. Each represents one of the four seasons. This 2020 “vintage” documents our stay here in our small hamlet of Bégot. Much like a vintage in winemaking tells you when the grapes have been harvested and processed, my ink’s vintage also captures a particular moment of time and place. Each holds a memory for me. A record that is personal and unique; the color will never happen in the exact same way again. Just like wine, weather conditions can affect the final color. The time of year you harvest, even the time of day can affect a plant’s final hue. My desire is to document my stay in France with a new vintage of inks each year. Next spring, I’ll begin my 2021 collection from our new home of Glandines, just a short drive from here but in a very different place and chapter in my life.

For those of us who enjoy a walk in the countryside, you might find yourself up against a hedgerow of blackthorn. Its thorns or daggers by a different name will stop you in your tracks. But the berry fruit of the blackthorn is very versatile. In late September here in France, sloes cover the branches like bunches of grapes. They soften after a frost and are not edible raw. But this ancestor to all plums is delicious when prepared with apples and lemon rind for a garnet-colored jelly. (Add to gin and sugar and store for three months for a liqueur come the holiday season.) For me, the pinkish purple dye produced by boiling the berries is a must-have in my dye kitchen. Fibers take the dye differently. You’ll arrive at a soft pink on wool but a vibrant purple on silk and cotton. Sloes produce an almost indelible ink that is fairly easy to procure. I keep bags of washed fruit in the freezer to be used whenever I need just the right shade of purple or another batch of my favorite jelly.

Making pigments from natural materials requires patience. You must harvest, prepare, and work the color for hours, days, or even months. Some plants, such as lichens, need a great deal of time to coax out their best color. Mostly, I use solar brewing for my dyes. Filling a large glass jar with washed and macerated flower petals, leaves, or hulls, and allowing them at least a month to be “cooked” by France’s southern sunshine. For a dye bath, the material is then strained and the fiber, yarn, or fabric is soaked for as long as needed to arrive at the desired color. For some dyes such as woad or indigo, the color intensifies with subsequent dips into the bath. For inks, the liquid is strained and simmered for hours to reduce the water content. The result is often a beautiful wash for writing or painting.

There is something special about an ink capturing a moment of time and place even before the pen meets the paper.

Armed with curiosity, an assortment of supplies, and a few recipes, I set out to make my own ink. I wanted to preserve the seasons here at Bégot, a tiny hamlet just north of Cahors in south west France. I am mindful of my surroundings when I forage. The code is: If you see a plant that is beautiful and exciting, don’t pick it right away. Wait until you come across it a few times and then harvest not more than 20% of the plant. Even if it seems like a simple weed, it might be something important to the ecosystem. Forage responsibly.

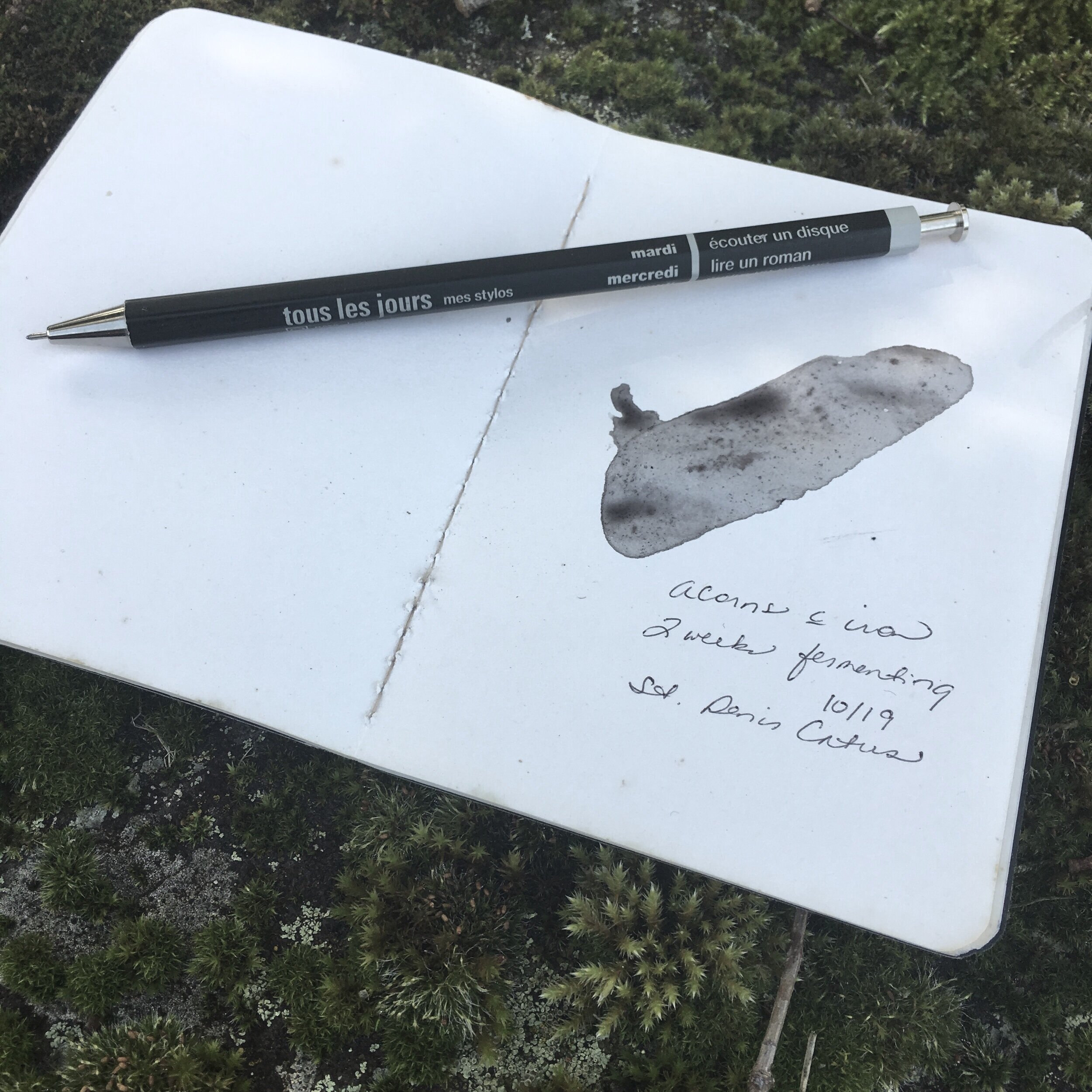

I made my first ink from last fall’s bountiful acorn supply. It’s oak tree territory here in the department of Lot so plenty of acorns to be found close to my front door. I gathered both the acorns and the caps. I found that the caps alone produced a grey color wash that I was looking for over a brown-grey hue. Experiment with each part of the plant because you might arrive at a different result. Also, you can add iron or alum to the bath to vary the range of hues. For iron, I add rusty bits and bobs to the plant material while it soaks. I also prepare the final bath in a large cast-iron dutch oven that I use only for my dye work. The iron mordant or fixative infuses into the material, creating a muted and darker color variation.

One dye bath can magically become a range of colors. I do document what I create in my dye kitchen, but not with the level of precision that I once did. Arriving at the same results is not as important to me now. Still, you might become frustrated by a pile of color chips and wonder, “Now how did I make that fabulous color?!” Keep a simple record. You’ll be glad you did.

Acorns make for an easy first ink. Contained within the acorns is tannin. Slow cooking acorns and / or their caps in water will allow the tannin to be released and give you the color you desire. The crockpot method works well for a slow processing of dyes and inks. Fill the crockpot half full with your foraged finds and top it off with water. Cook for 3-7 days and keep adding water as needed. You want the plant material to remain covered. There may be an odor so this is best done outdoors or in a garage or barn. Be sure that the equipment you use for your dye work is only used for that purpose. No making acorn cap dye in your crockpot one week and goulash the next.

Ink is such a humble liquid. Considered merely an element of the modern world, given the availability of our disposable pens and printer cartridges, we don’t see it as a historical marker. But ink has contributed more to the growth of civilization than any other human creation. Let’s consider its origins for a moment. Archeologists discovered pigments and mixing tools from 400,000 BCE in Zambia. With no known images from that time, we look to the early cave paintings in France dated to approximately 35,000 BCE. Charcoal from burnt sticks, crushed clays and soils, applied with simple brushes and by blowing paint held in the mouth left our earliest historical record of people’s lives.

Over the last three millennia, alphabets and languages expanded in order to meet the demands of trade, law and recording history and traditions. Examples can be found on shards of Chinese pottery, Sumerian clay cylinders, and Egyptian papyrus. An early “common ink” was made from oak galls. Galls are a growth on oak trees that are made when insects puncture the branches. Some of the earliest recipes to make ink come from Pliny the Elder, a 1st-century Roman author. The Dead Sea scrolls, the Codex Sinaiticus (the oldest and most complete Bible believed to be written in the 4th century), medieval manuscripts, da Vinci’s sketches, the Magna Carta, the Declaration of Independence all contain iron gall ink.

You connect with history when you write with natural inks.

The Egyptians dyed the cloth that they used to wrap mummies with woad or known as pastel here in France. By some accounts, woad was the source for the body paint used by Celtic warriors to confront Roman invaders. Centuries later, Medieval European cities such as Toulouse grew in wealth and population thanks in part to the profits of the lucrative pastel trade. During the extraction process, the dye sediment settles on the bottom of the dye bath. Dried, it can be stored and used when needed to make ink or dye. It’s precious to my ink collection.

Woad or pastel (Isatis tinctoria) is a member of the mustard family. Very easy to grow but tedious to produce the color. Harvest the leaves in the heat of summer. Chop and soak in an alkaline bath. Urine was the element of choice in Renaissance France but for a less unpleasant smell, I use a few teaspoons of soda ash dissolved in hot water before adding to the dye bath. The liquid needs to be agitated in order to cause oxidation. A simple hand whisk will do when preparing a small batch but you have whisk vigorously for 15-20 minutes. The liquid will be green in color. The magic of the dye process happens when a fabric or fiber is dipped into the bath and then pulled out to dry in the air. With oxidation, it will turn from green to a beautiful shade of blue. Multiple dips produce a deeper color.

Ink making is an art form. A chance to experiment and transform one thing into another. Consider the process of pulling color from lichens. I forage for different varieties after a wind storm. They are blown from their branches and are easily gathered on the ground. I never harvest lichens from the trees, themselves. You can soak the lichens in water, simmer them over a low heat, but you might not arrive at a worthwhile color. Ammonia is what pulls the pigment out of most lichens. I use a 1:2 part solution of ammonia to water in a glass jar. At first, you’ll have a pretty yellow color. As one month turns into two, the yellow develops into a deep brownish-red. Wait three months or more and a lichen such as Oakmoss - which is neither a moss nor does it grow on oak trees - will develop into a deep purple ink. I keep several jars going at the same time. For the chemical reaction to work, you need to allow air to come into the jar. I stir them weekly and leave the lid cracked. Store them in an outdoor shed due to the ammonia fumes. This is not a dye to keep in your kitchen pantry.

Oakmoss (Evernia prunastri) lives on the bark of deciduous trees. The common name is Staghorn lichen because its shape resembles the antlers of deer. At one time, Oakmoss was popular in the perfume industry, valued for its rich and earthy aroma. However, this lichen can produce a severe reaction in people with sensitive skin. Be careful when working with it and wear gloves, eye protection, and mask. (All things we have in our homes now given the pandemic. Heavy sigh.)

This year has found me to be both forager and lover of handmade ink. I adore the simple pleasure of putting pen to paper to communicate an idea. When done with an ink I’ve made, a memory is infused alongside the written sentiment. Taking a brush to canvas to see what might happen when subtle, one-of-a-kind, foraged colors meet one another, connect with oxygen, and dry to the touch is a serendipitous delight. I approach the process of ink making with a sense of “let’s see what happens.” I’m open to the unexpected possibilities.

In many ways, this artistic endeavor is a metaphor for my life in France. Transformation. Enjoy the journey. Let go of expectations. What started with gathering acorn caps under a beautiful old oak tree developed into my first collection of one-of-a-kind inks, allowing me to document my time here in this place. You don’t have to live in south west France to make ink. You don’t have to have access to a forest to make ink. Color is all around you. Wherever there might be a natural plant growing, there is that possibility that it could yield a hue.

The more you slow down and look, the more you will find. Thankfully, 2020 has given us the precious gift of time.

Embrace it.

Learn something new.

Make something by hand.

À bientôt,

Karen

I add a blog post quarterly to Karen’s Atelier - more or less with the changing seasons. For a weekly dose of something "short and sweet" and a nod to French culture, be sure to subscribe to my Weekly Voilàs on this website. For those that have already subscribed, merci. Your support encourages me to take the next step in “living a french life.” It is a privilege to share this journey with you.